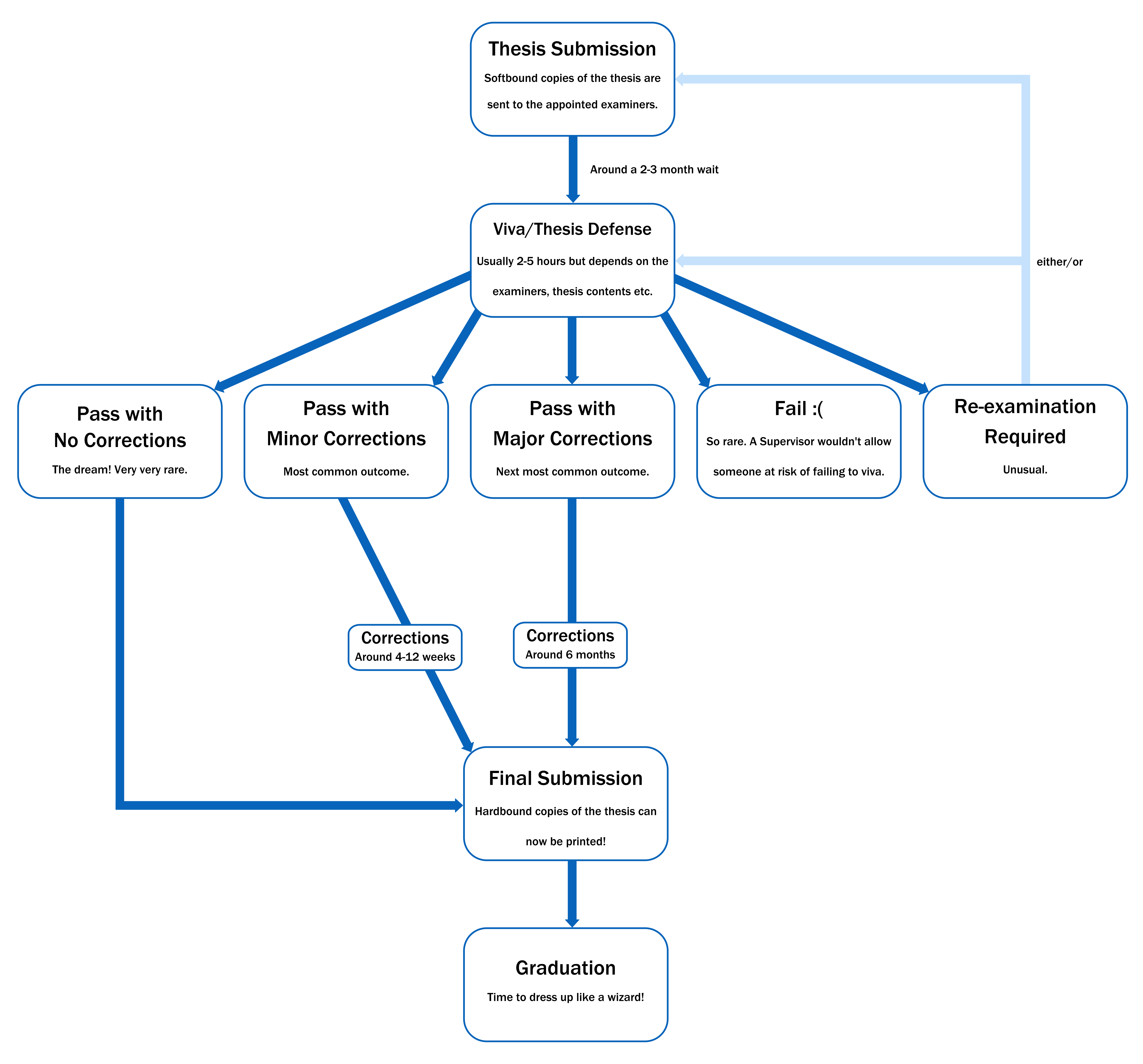

Oh geez, I haven’t updated my blog since June. The reason is that I’ve been really busy finishing my PhD. It’s a rather drawn-out process which confused many of my friends and family. After I handed in at the end of September lots of people were excitedly asking if I’d finished. Then I had to explain, well sort of but not completely; I still have a viva and will then probably have to do corrections. I’ve therefore made this flow chart which I’m hoping will help others explain it.

NB- This only refers to PhDs in the UK. It’s different elsewhere.

Writing Up Period

What’s talked about being the convention for PhD students is to finish lab work about 3 months before their submission deadline so they can then focus solely on writing up. Many of the students in my cohort did this but I didn’t. I faced a 2 month delay at the beginning of 2018 because a piece of equipment I needed to use to finish my study was faulty. I couldn’t do much else in that time, so I started writing (including a review article which made up most of my thesis introduction).

Submission Date Versus End of Funding

For full-time PhD students in the UK, we usually have a fixed submission deadline of 4 years after beginning the PhD. As I was on a 4 year PhD programme (6 months taught component + 3.5 year PhD project), my submission deadline of the 30th September 2018 also coincided with the end of my funding. Many charity funded PhD studentships (including British Heart Foundation and Alzheimer’s Society) are 3 years so candidates could spend 12 months writing up, they just wouldn’t get paid.

Thesis Format

In the UK, most PhD student will write up a traditional format thesis consisting of the following chapters: general introduction covering what is known about the research area and the key scientific concepts; methods chapter detailing the included experimental work; results (usually divided into 3 or 4 chapters but very dependent on the project) and a general discussion summarising all the experimental work, what it means, what the limitations are and the future directions. At some UK universities including Manchester, Birmingham and Bath it is also possible to submit an alternative format thesis. As with a traditional thesis, this is required to have a general introduction and discussion. However, instead of separate methods and results chapters, it then allows you to include papers that have already been published and/or work written up in a format for publication. Each of these will be a separate results chapter containing introduction, methods, results and discussion sections.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each format. I decided to write up in alternative format because I had two published papers which I wanted to include. I also wanted more experience of writing papers which is something you will do for the rest of your career if you choose to stay in academia as opposed to writing a traditional thesis which you only do once. A disadvantage of the alternative format is that it can end up lacking detail. Not all the experimental work conducted makes it into the final publication. One big reason for this is that experiments inevitably don’t work first time around and need to be optimised. A way you can get around this with an alternative format thesis, is to include the optimisation and characterisation work in appendices.

Viva Format

In the UK we refer the the oral exam at the end of a PhD as a viva, short for viva voce which means ‘by live voice’ in Latin. After submitting your thesis, copies are sent to your two examiners: an external from another university who is an expert in your field of research and an internal who is an academic at your institution who usually works in a related field but doesn’t have to be an expert. Everybody will have a very different viva experience because it’s so dependent on your examiners, your thesis content, how you present your work etc. The examiner’s job is to confirm you have done the work presented in your thesis, assess your knowledge of your research and identify what could be improved upon (it’s so rare to get no corrections). It’s common to begin the viva with a presentation. I gave a short one (10 minutes) summarising the key results of my thesis but I’ve heard of candidates giving 45+ minute presentations. The examiners will then usually go through your thesis section by section, asking questions such as:

- Can you tell us more about X?

- Why did you do choose to do this particular experiment?

- What are the limitations of this method?

- What future experiments could be done?

Then usually between 2-5 hours later, the examiners will ask you to leave the room so they confer (that part is excruciating!). When they bring you back into the room they will then tell you you’ve passed (failing is so exceedingly rare) and what corrections you need to do. Next, you can then go celebrate with your lab. If you have a great supervisor like I did, they’ll crack out not one, but two bottles of Prosecco.